INTESTINAL VILLI WITH BACTERIA

Microbiome Terminology

The terminology describing the microbiome has evolved based on advances in research. The definitions below represent the most recent terminology reflected in current scientific literature and expert consensus statements.

The microbiome is the full collection of the microorganisms (the microbiota), their genes, and their microenvironment (habitat) in a specific area. Analysis of the genetic material is how most recent studies identify the microbiota, but the terms microbiome and microbiota are often used interchangeably except in scientific research.1 Subsets of the microbiome include the virome (viruses), mycobiome (fungi) and archaeome (archeae; these organisms resemble bacteria, but are a distinct domain).2 It is a dynamic environment with complex interactions and interconnected metabolisms.3

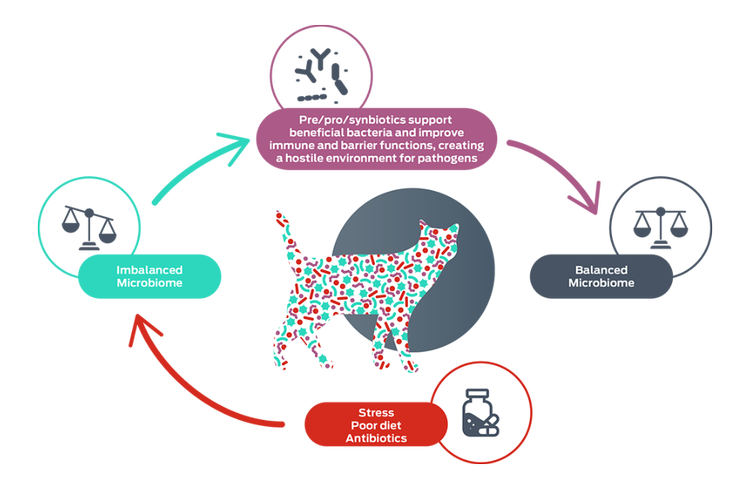

Maintaining a diverse and balanced population of gut bacteria is essential for good health.

Dysbiosis is an imbalance of the microbiome and may have adverse effects on host health.4 Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome has been associated with gastrointestinal infections, obesity, allergies, auto-immune conditions, cognitive impairments, chronic enteropathies, and others.4,5 However, whether this association represents causation or only correlation – whether dysbiosis is a symptom or cause – remains to be seen.5

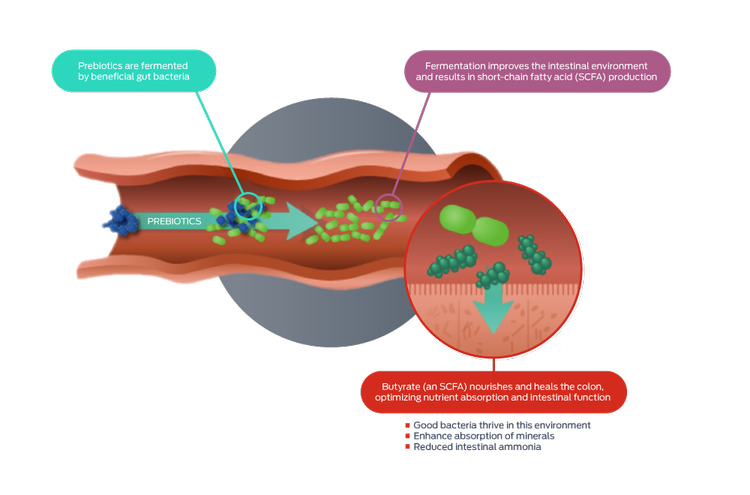

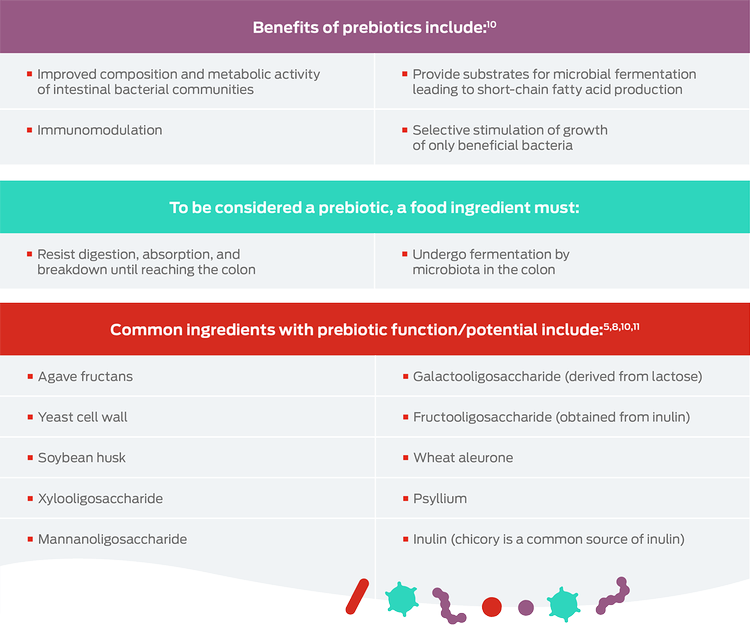

Prebiotics are substrates – such as fiber and resistant starch – that are selectively utilized by the host microorganisms, conferring a health benefit.6-8

The ultimate aim of prebiotic supplementation is the enhancement of the gut microbiota: however, prebiotics have beneficial effects of their own, including improving the health of the gut itself. The primary products of bacterial prebiotic metabolism include short-chain fatty acids – such as butyrate and propionate – which have beneficial effects.9 Prebiotics also interact directly with host cells, modulating immune and gut epithelial cell signaling, regulating inflammation and barrier function.9

Prebiotics facilitate specific changes, both in the composition and/or activity of the gut microflora, that confer benefits upon host well-being and health.8

Purina's prebiotics

The most commonly used prebiotics are fermentable, non-digestible carbohydrates.

Purina uses purified inulin, wheat aleurone, chicory root and psyllium as prebiotics. Inulin is extracted from chicory root using a hot water process and by further processing, oligofructose is extracted. Naturally high concentrations of inulin can also be found in garlic, onion, artichokes and leeks. Wheat aleurone is found as the single layer of cells between the bran and endosperm of the wheat grain.

Probiotics are an example of a nutritional intervention that can help, through a variety of mechanisms, to reduce pathogen overgrowth and shift the microbiota toward more beneficial bacterial species.8,9,13

In recent years, probiotics have emerged as a safe and novel way of maintaining a healthy intestinal microbiota and therefore promoting good pet health. The technical definition of probiotics is: "live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host."12 Probiotics can exert beneficial effects on the microbiome with colonization.9

To date, the majority of available probiotics are members of the Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus genera.8 Different probiotics have different benefits, and a probiotic should be chosen based on the desired end benefit. Even within the same species, some bacteria can have probiotic benefits while others do not; therefore, it is important to test the efficacy of the strain to determine potential benefits.

Synbiotics combine prebiotics and probiotics.

The combinations may be complementary (the prebiotic and probiotic have independent mechanisms and benefits) or synergistic (containing a prebiotic that is the preferred substrate for the accompanying probiotic).9

Postbiotics are preparations of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confer a health benefit on the host.14

According to the International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), postbiotics are deliberately inactivated microbial cells, with or without metabolites or cell components, that contribute to demonstrated heath benefits.14 They do not need to be derived from probiotics, and purified microbial metabolites do not qualify as postbiotics.14 Despite their inability to replicate, postbiotics may induce beneficial modulation of the microbiome.14 Postbiotics may enhance epithelial barrier function, modulate systemic metabolic responses, and modulate local and systemic immune responses.14 In addition, there is evidence suggesting postbiotics affect the gut-brain axis.14 Postbiotics offer an alternative when the use of live probiotics is not indicated.8,14 Postbiotics are stable and have a long shelf life, and some may not lose their bioactivity when co-administered with antibiotics or antifungals.8,14 Like probiotics, the effects of postbiotics are strain-specific. A live probiotic and its postbiotic counterpart don’t necessarily have similar properties, and effective postbiotics are not required to be derived from strains with known probiotic effects.

Non-replicating microorganisms (NRMs) are heat-treated microorganisms, together with their culture medium, that are known to positively influence health even after they have been inactivated (rendered incapable of replicating) and are therefore considered postbiotics.14

Explore other areas of the Microbiome Forum

Find out more

- Marchesi, J. R. & Ravel, J. (2015). The vocabulary of microbiome research: a proposal. Microbiome, 3, 31. doi:10.1186/s40168-015-0095-5

- Kim, J. Y., Whon, T. W., Lim, M. Y., Kim, Y. B., Kim, N., Kwo, M.-S.,…Na, Y.-D. (2020). The human gut archaeome: identification of diverse haloarchaea in Korean subjects. Microbiome, 8, 114. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00894-x

- Seth, E. C., & Taga, M. E. (2014). Nutrient cross-feeding in the microbial world. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5, 350. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00350

- Belas, A., Marques, C., & Pomba, C. (2020). The gut microbiome and antimicrobial resistance in companion animals. In Duarte, A. & Lopes da Costa, L. (Eds.), Advances in Animal Health, Medicine and Production (1st ed.), pp. 233—245. Springer International Publishing

- Pilla, R., & Suchodolski, J. S. (2021). The gut microbiome of dogs and cats, and the influence of diet. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice, 51(3), 605621. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2021.01.002

- Valcheva, R., & Dieleman, L. A. (2016). Prebiotics: Definition and protective mechanisms. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 30, 2737. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2016.02.2008

- Barros, C. P., Guimarães, J. T., Esmerino, E. A., Duarte, M. C. K. H., Silva, M. C., Silva, R.,…Cruz, A. G. (2020). Paraprobiotics and postbiotics: concepts and potential applications in dairy products. Current Opinion in Food Science, 32, 18. doi:10.1016/j.cofs.2019.12.003

- Wegh, C. A. M., Geerlings, S. Y., Knol, J., Roeselers, G., & Belzer, C. (2019). Postbiotics and their potential applications in early life nutrition and beyond. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20, 4673. doi:10.3390/ijms20194673

- Cunningham, M., Azcarate-Peril, M. A., Barnard, A., Benoit, V., Grimaldi, R., Guyonnet, D.,…Gibson, G. R. (2021). Shaping the future of probiotics and prebiotics. Trends in Microbiology, Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2021.01.003

- Santana Vaz Rezende, E., Carielo Lima, G., & Veloso Naves, M. M. (2021). Dietary fibers as beneficial microbiota modulators: a proposal classification by prebiotic categories. Nutrition, 89, 111217. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2021.111217

- Jalanka, J., Major, G., Murray, K., Singh, G., Nowak, A., Kurtz, C.,…Spiller, R. (2019). The effect of psyllium husk on intestinal microbiota in constipated patients and healthy controls. International Journal of Molecular Science, 20(2), 433. doi:10.3390.ijms20020433

- World Health Organization (WHO) & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States (FAO). (2006). Probiotics in food: Health and nutritional properties and guidelines for evaluation. (ISSN 0254-4725)

- Sanders, M. E. (2008). Probiotics: Definition, sources, selection, and uses. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 46 (Suppl 2), S58–61. doi:10.1086/52334.

- Salminen, S., Collado, M. C., Endo, A., Hill, C., Lebeer, S., Quigley, E. M. M.,…Vinderola, G. (2021). The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 18, 649-667. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00440-6